Cairo Contemporary Music Days 2017

In collaboration with Goethe-Institut Cairo

Friday, April 28 -19.00 Goethe-Institut Cairo 17 Hussein Wasef, Mesaha Square, Ad Doqi

Music Talks II

Dr: Doris Kösterke

The Beginnings of “New music” in Darmstadt, Germany, after World War II

Why isn’t it just nice?

Non-commercial contemporary is no easy listening.

One historical reason for that is the birth of “New Music” out of the ruins of World-War-II.

When, in 1946 in a German city called Darmstadt, the first summer courses for international new music took place, German people had suffered twelve years of dictatorship that abused also music for purposes of political propaganda.

Hitler had used traditional music, both folk and artificial, to create a collective self-confidence of being German among the desperate people.

The official news in the radio was decorated with music of Beethoven.

Hitler himself loved to attend the “heroic” operas of Richard Wagner at Bayreuth. So “the folk” tried to like Wagner as well. Children and young people were organized in groups that prepared them to their roles in a “glorious” future, the boys and young men as brave soldiers, the girls and young women to be modest, strenuous and fertile. All had to sing a lot of folksongs to keep the group together and most of them liked that because of the good mood it made. (Please mind my irony!)

Composers had to write a non-complicated music that should easily enter the ears of “simple people”.

Any kind of art, that seemed to be able to make people think, was forbidden.

Critical artists were forced into labour camps to do something Hitler considered to be useful.

Some were as lucky as to be able to leave the country.

When the war was over, people were thirsty for arts. But traditional music seemed contaminated through its capability for abuse.

Artists were seriously concerned with the question: what can we do that totalitarianism will never take place again?

Those younger generation, among those are Luigi Nono, Maurizio Kagel, Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Hans-Werner Henze, are often considered to be rather philosophers than musicians. Bernd Alois Zimmermann even considered poets, musicians and painters to be the only true philosophers.

They wanted to write a “New music” that was different from any music that could be used for propaganda purposes.

In collaboration with some hard-core-philosophers around Theodor W. Adorno, they spoke of “critical composing” as of a custom of composing, that reflects its own political relevance.

Some others headed towards an “objective composing” that, in opposite of an emotionally based romantical composing, was based on systems of tones, rhythms, dynamics and timbres, analogue to the twelve-tone-row used by Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils Anton von Webern and Alban Berg. Some others referred to Schoenberg as to a great moralist in music. In German musicology we write this kind of “New music” with a big “N”, while “new music”, with a small “n”, just means contemporary music in general.

I refer to “New Music”, with a big “N”, as to a means that wants to make people more critical. That wants to plant antennas for sensitivity – not only for music, but even for the rest of the world.

For that purpose music should not be simple. And it should not be just nice: According to a Russian writer, the plough of thought goes over nice things without gripping something.

It makes you more alert to manipulation by totalitarianisms of today, not only the political ones.

(Commercialization can be one of them)

Dr. Doris Kösterke

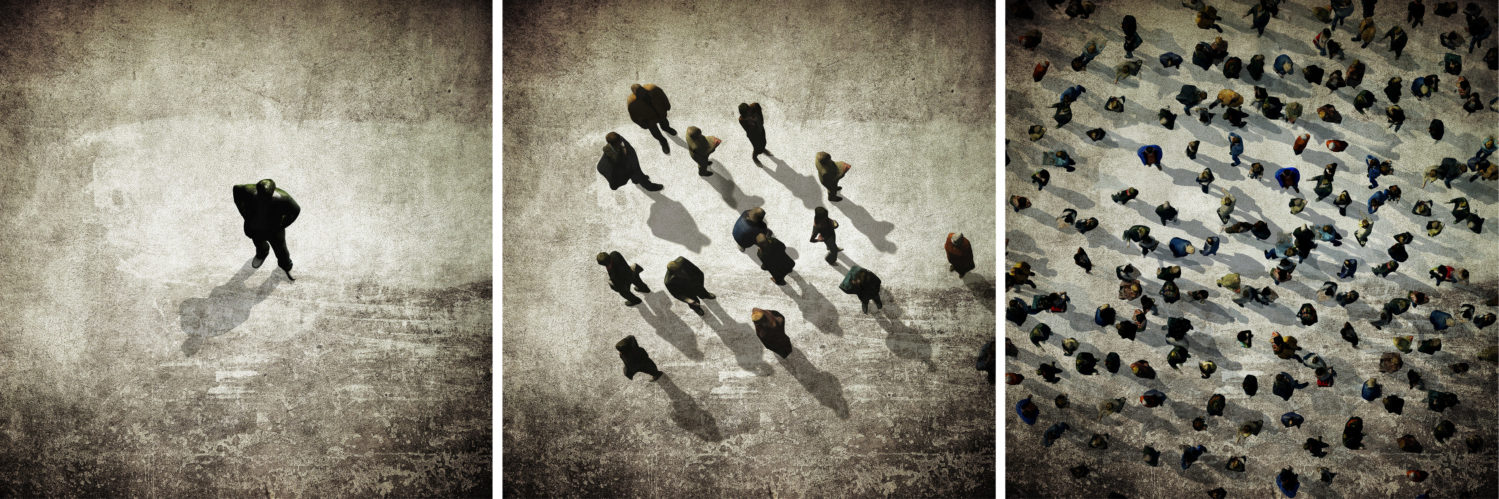

Photo –

( July 1957, 12th International Vacation Courses for New Music, Seminar: Karlheinz Stockhausen) Bundesarchiv B145